How should we tax the rich?

There are now incredibly creative ways of taxing wealth. Is it time that we listened to such ideas?

It is fascinating to see support for a policy, especially when that support justified the policy in the first place, collapse in the space of hours.

This is exactly what happened last week, when the UK announced an increase in National Insurance Contributions by 1.25 percentage points for employed and self-employed people earning more than £9,568. Prime Minister Boris Johnson, who is known for doing policy-by-polling, reckoned that the 64% of those found by Ipsos Mori in August to support an increase in NICs to pay for social care gave him the legitimacy to row back on his previous manifesto pledge which ruled out any increase in major taxes.

That all dissolved upon contact with reality, when the policy was announced in full. It was attacked from all wings of the political spectrum, with the Labour left hitting on some fairly punchy attack lines around broken promises and hampering working people.

The likes of Owen Jones and Ash Sarkar did an almost synchronised media round saying the government should ‘tax the rich’ in the form of a wealth tax. Whilst Jones and Sarkar (rather not surprisingly) didn’t massively detail their proposition, it is worth considering what a wealth tax may look like.

Wealth taxes can take many forms and:

Could be specific to property, a specific asset, or all assets

Could be one-off or annual

Could be a tax on returns to wealth (e.g. dividends, rent, asset value increases), or on transfers of wealth (e.g. inheritance, gifts, property sales)

To me, this exhibits why arguments about whether a wealth tax is justified or not are largely pointless.

The range of different kinds of wealth taxes mean that not all of these taxes would have the same effect on economic efficiency or inequality. Therefore, drilling a little bit deeper may help us to work out what (if any) would be the right approach.

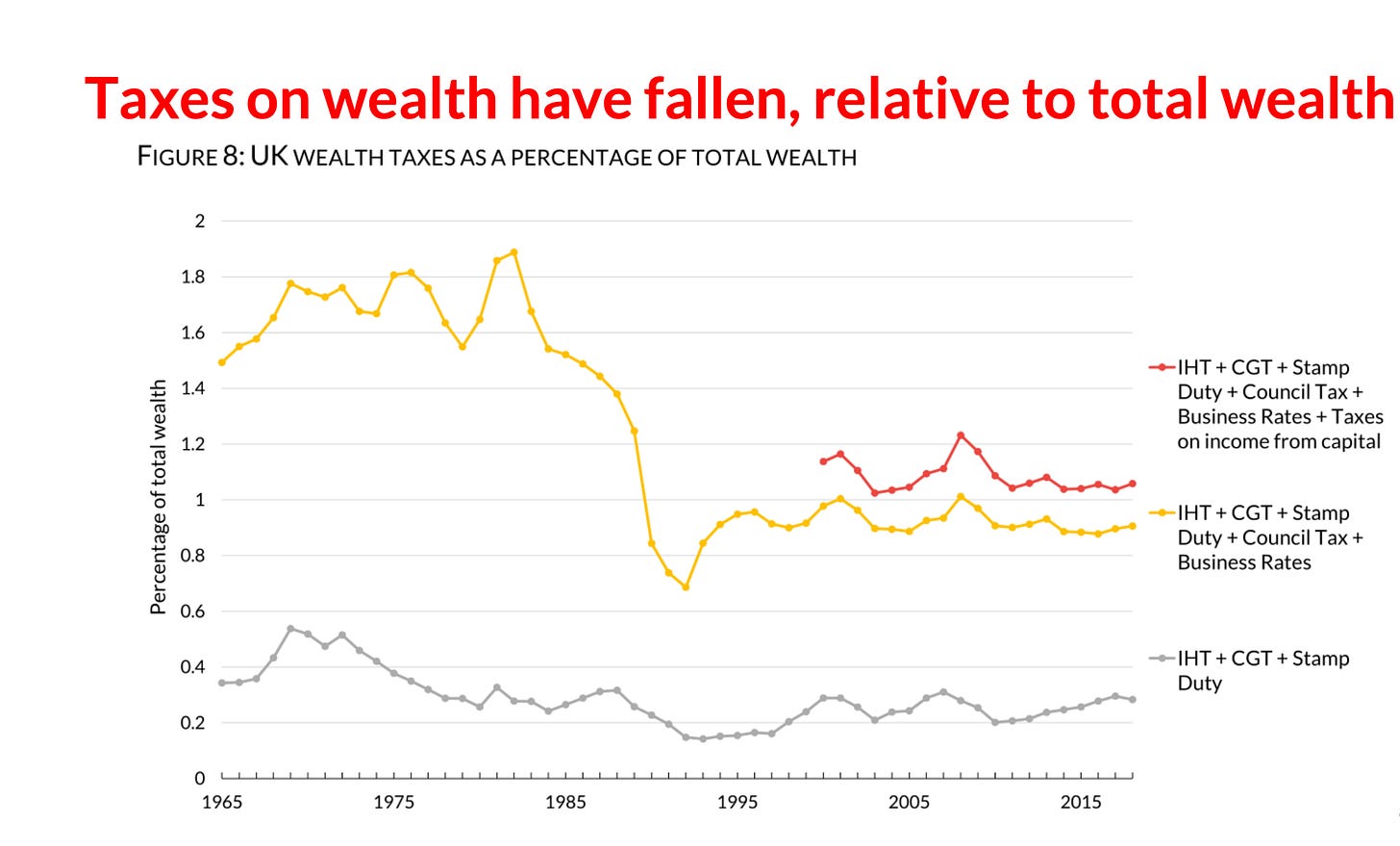

Advani, Chamberlain, O’Donnell, Miller. (2020)

So, assuming that wealth taxes become an increasingly important part of fiscal policy (which is perhaps a questionable assumption), what is the best form they could take?

A proportional property tax

Council tax is arbitrary and unfair. With bandings based on ancient valuations, they often are not even proportional to modern property values, and as a result, lower bands pay, proportionately, far more.

As Vince Cable notes, the average British household pays no more than 0.2% of their home’s value in council tax. However, there are 41 constituencies in the north and Midlands in which the average household’s council tax burden is 1% or higher.

A PPT would therefore examine the value of a home and tax it at around 0.5%, replacing both council tax and stamp duty (for the record, the abolition of stamp duty could stimulate as much as £10bn in economic growth).

Taxing land properly would signal a tectonic shift in Britain’s political economy. Land is a fixed asset, and wouldn’t yield the same disincentives as if you tax production or consumption. The only thing a land tax really disincentives is property speculation - something that most of us could do without.

A more unique extension of this idea can be found in Glen Weyl and Eric Posner's book: Radical Markets.

According to Sam Bowman’s review of the book in CapX:

“Weyl and Posner suggest a system of taxation where, in principle, everything is available to buy, all the time. A homeowner or patent holder, for example, must declare the price they would sell their house or patent for – and if someone comes along and offers them that, they will have to sell. Assets are taxed annually on that valuation – they suggest a rate of 7 per cent – with the proceeds distributed evenly among a country’s citizens via a cash ‘dividend’.”

This Common Ownership Self-Assessed Tax would mean that individuals would be incentivised to put a really accurate personal valuation on their assets. Place too high a valuation and they get a mega tax bill. Place too low a valuation and they may well have to sell-up.

As a result, according to Posner and Weyl, economic efficiency is maximised. People that actually want to build on land or use an asset productively will be the ones that get to use it, rather than those who sit on them, merely expecting greater and greater returns.

One-off tax

Depending on the efficiency of your tax system, levels of inequality, and the state of your public spending, a one-off wealth tax might be a better proposition than one that takes place infinitely.

This is an idea that has been posed by the Wealth Tax Commission, whose team includes the likes of Arun Advani, Emma Chamberlain, and Gemma Tetlow.

Such a tax would cover all assets, including private homes and pensions, but minus any debts such as mortgages.

Whilst not advocating a specific rate, a one-off tax of 1% a year for five years would raise £260bn. This would be more than enough to tackle the Covid-19 backlog, with the NHS needing around £10bn a year extra over the next three years.

One-off taxes of this kind are also much more difficult to avoid, since they are based on behaviour that has already occurred, and past valuations.

The Commission has their own interactive website that allows members of the public to model their own revenue-raising options.

The efficiency of this tax may depend on whether citizens truly think that this tax is a one-off, which would be a problem given Britain’s current political climate. The perception of the Labour Party by much of the public is that they would tax your gran’s dodgy knee if they had the chance, whilst the Conservatives hardly have a reputation for sticking to promises (as last week’s tax debacle has shown).

Secondly, the politics in play may create immense pressure to maintain the tax. With an ageing population, and a worsening climate crisis potentially throwing up the demands for unprecedented government spending, pulling up the drawbridge from hundreds of billions worth of pounds would be a tough sell to the Treasury.

Windfall tax on tech giants

Big economic upheavals tend to lead to higher short-run levels of inequality. The likelihood is there will be no difference as technology companies become increasingly more successful.

If Artificial Intelligence explodes in importance in the way that many researchers believe it will, a series of global oligopolies will form, making the likes of Amazon, Apple and Google look like relative SMEs.

A paper at Oxford’s Future of Humanity Institute recognises this, and proposes a Windfall Clause in order to counter some of the immense levels of wealth that would accumulate in the hands of a small number of firms.

“By voluntarily adopting the Windfall Clause, firms would bindingly agree to donate a meaningful portion of their profits if they earn a historically unprecedented economic windfall from the development of advanced AI. We define a “windfall” as a level of income greater than a substantial fraction (e.g., at least 1%) of the world’s total economic output. It is unlikely, but not implausible, that such a windfall will occur. As such, the Windfall Clause is designed to address a narrow set of low-probability future scenarios which, if they came to pass, would be unprecedentedly disruptive.”

The rate at which you would pay would also increase as a company's share of global output rose.

For a simplified example, suppose that a signatory earns a $5 trillion (in 2010 dollars) profit from AI in 2060.

Based on OECD estimates, the Global World Profit (GWP) in 2060 will be $268 trillion (again in 2010 dollars). Thus, the signatory’s profits would be 1.8% of GWP.

According to this Function, they would be obligated to give

0% of its first $268 billion in profits, for a subtotal of $0;

1% of its next $2.412 trillion in profits, for a subtotal of $24.12 billion;

20% of its next $2.32 trillion in profits, for a subtotal of $464 billion

for a grand total of $488.12 billion.

This is a substantial amount of money that could accomplish a lot of good in the world. It could deal with concerns around structural unemployment from automation, mitigate potential increases in inequality, and raise funding for detailing with other issues such as the climate crisis.

The paper deals with several strong criticisms of this proposal, including the extent to which such a clause could be ‘voluntarily’ signed-up for, whether these payments could be evaded through the paying out of dividends, and whether this would reduce the incentive for these kinds of companies to innovate.

Two further issues arise in my mind that weren’t alluded to in the paper. The first is that these sorts of taxes will only be credibly available in the future, not right now. This is because global oligopolies of this sort have not formed yet (this is not to say that currently large technology companies should not be hit with better-designed taxes right now, they absolutely should!). As a result, funding important issues at this very moment could not come from a tax like this.

The second concern I have with this policy concerns pre-distribution. Is it right to allow companies to get this large in the first place? Is it not a better idea to change the underlying structure of the economy so that all companies can blossom, rather than generating an unlevel playing field that is then sorted out ex-post?

In my mind, the answer to that question fundamentally depends on the kinds of firms that generate this immense value. If a company came up with a medical procedure that could extend the lives of people by 50 high-quality years, then I am all for them getting filthy rich, providing that this technology is fairly widely available. If it is simply the next TikTok, then it can get in the bin.

That however, is a question for democratic discourse, But it is a question that will build into a crescendo if wealth continues to concentrate in the way that it is doing so. ‘Tax the rich’ is clearly a vacuous slogan, but who we count as the rich, and how they should be taxed, are extremely important questions.

Of the Week - My Favourites

Podcast: Tortoise Media (Basia Cummings) - Orphaned by America

Youtube Video: Shiey - Journey Through Modern-Day Ghost Town of Italy

Song: Little Simz - Point and Kill

Banging new album, and NPR Tiny Desk if you are into that sort of thing.

Article: Sam Bowman, John Myers & Ben Southwood (Works in Progress) - The housing theory of everything

Works In Progress is a great new online magazine funded by Tyler Cowen’s Emergent Ventures programme. It helps to tell stories of the big picture and the incremental, around progress, with some really original thinkers. Their bumper essay on housing as a systemic economic problem is a great exposition of their insightful, evidence-based flair.